The Development of Sensory-Motor Coordination in Social Interaction

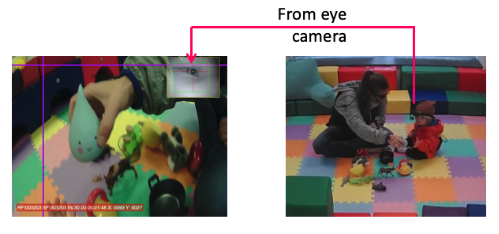

In this study, we want to understand how infants develop their sensory-motor coordination skills in everyday social interaction with their caregivers. We invited infant-parent dyads to our lab to participate in an object-play experiment where both the child and the parent wore head-mounted eye-trackers (from Positive Science and Pupil Labs) and motion tracking system (from Polhemus Liberty) affixed to the eye-tracker on the right temple or the participants’ head and both of their hands. They were then asked to play with several objects naturally as they would at home (see Figure below).

This experimental paradigm was first implemented in a simple laboratory setup to facilitate automatic object detection in egocentric videos and later was expaned to a more naturalistic home-like environment.

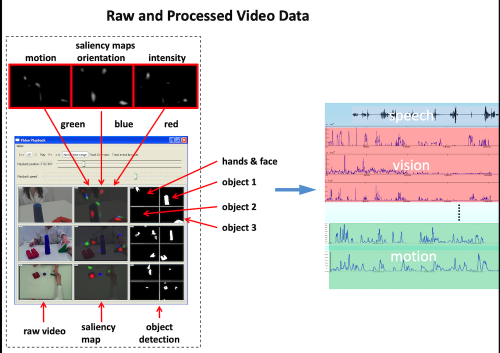

With the wearable sensors and a multi-view camera capture system (from Geovision), we collected first-person visual input recordings at 30 Hz, moment-to-moment precise eye-tracking data at 30 Hz, and hand and head motion tracking data at 60 Hz. After four play sessions, the children also participated in a test phase. They were asked to choose the correct visual stimulus when the experimenter asked the children to point to or give them the object referenced by the novel label.

This toy-play interaction is one of the most common everyday activities in children’ lives. Thus, this setup gives us a valuable representation of how learning happens in the real world from the child’s point of view.

After data collection and preprocessing, we developed scripts to automatically detect and segment the objects from infants’ first-person view recordings and compute scene structures and perceptual characteristics from infant’s first-person view. We investigated what types of visual characteristics (either generated by the children’s own bodily movements or by the parents’) drive children’s real-time attention and contribute to the successful encoding and recognition of the novel objects.

We also had a series of experiments in different conditions where we manipulated the objects’ properties by: 1) asking the parents to sit on the side and just let children play on their own, so that the visual-motional experience is solely created by the children; 2) manipulating the weights of the objects to make them harder for the participants to rotate and handle. Some of these research projects were published in the Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, Annual Meetings of the Cognitive Science Society, and International Conference on Development and Learning.